- What the developing world needs today is accelerated, inclusive growth through rapid yet sustainable transformation, using the instruments of game-changing inclusive innovation. Pandemic has pushed hundreds of millions of families from poverty to extreme poverty and we need to give special weightage to innovation that can create the magic of ‘access equality’ despite ‘income inequality’. Much of it could be non-technological innovation.

- The geography of new knowledge creation is shifting from the developed world to talent-rich parts of the developing world. India, for instance, is becoming a global R&D hub, with over 1,200 multinational companies setting their R&D centers in India.

The Global Innovation Index (GII) provides detailed metrics about the innovation performance of 131 countries and economies around the world. Its 80 indicators explore broad dimensions of innovation, including political environment, education, infrastructure, and business sophistication. GII has done an outstanding job in terms of bringing innovation from the periphery to the core in terms of thinking around the globe. It is continually and consciously improving its measurement matrix, but a lot more can be done by considering multiple dimensions of innovation. Here are a few thoughts.

GII defines innovation as follows: “An innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), a new process, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation, or external relations.”

The current GII matrix does not evaluate that spectrum of the innovation highlighted above in bold letters. And yet, such non-technological innovations can make such a huge difference.

Take, for instance, a new business practice or business model innovation. We know that Uber, AirBnb, Netflix, Skype, Zoom, etc. have had an impact that is orders of magnitude higher than those from purely technological innovations.

Innovation’s multiple dimensions include technological innovation, business model innovation, workflow innovation, system delivery elevation, organisational innovation, policy innovation, grassroots innovation, social innovation, etc. In fact, it is a combination of all of these that can make a transformational difference.

Take, for instance, the Indian example of the world’s fastest and largest financial inclusion initiative, JAM for short. It stands for J (Jan Dhan Yojana, a policy initiative), A (Aadhar, a Unique Identity Number, for a billion Indians), and M (Mobile, a billion of them), which created 360 million-plus bank accounts in record time, covering the bottom of the pyramid excluded population. It even won the Guinness book of records certificate. Moreover, during the pandemic closedown, it helped the government to do direct transfers to millions of these accounts, thus avoiding extreme hardships. If you look at it closely, JAM was a combination of technological innovation, workflow innovation, system delivery innovation, and policy innovation.

Reliance Industries, India’s largest private-sector enterprise, launched Jio, which lifted India from 155th position to the first position in mobile data transmission in just a few months. Indians now have access to the cheapest data in the world, some even with free voice calls. This massive digital inclusion of all those who were excluded was possible again with a combination of technological, workflow, and system delivery innovation. Jio on-boarded 50 million customers in 83 days, which stands as a world record today.

However, neither JAM nor JIO creating these massive financial and digital transformational initiatives can be counted in the currently used innovation matrix of GII.

What the developing world needs today is accelerated, inclusive growth through rapid yet sustainable transformation, using the instruments of game-changing inclusive innovation. This is even more urgent now, as the pandemic has pushed hundreds of millions of families from poverty to extreme poverty.

This is where we need to give special weightage to innovation that can create the magic of ‘access equality’ despite ‘income inequality’. Much of it could be non-technological innovation.

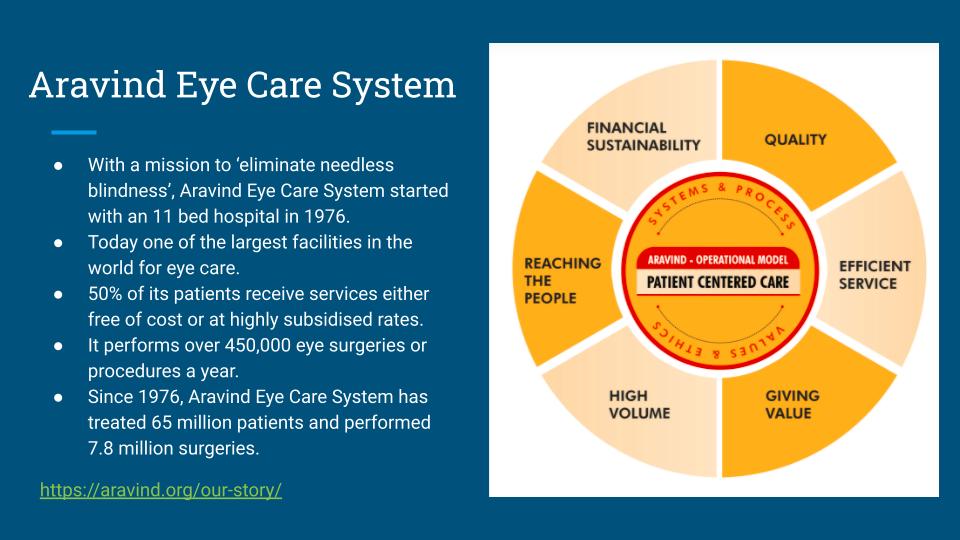

Take for instance, workflow innovation, which is used by Arvind Eye Care to do high-quality cataract surgery. It costs per person just $30, not $3,000, as in the developed world. Quality-wise, it beats the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. This innovation uses an assembly line approach, inspired by McDonald’s. It has spread to 17 countries now. Similarly, workflow innovation is deployed by Narayana Health, which does heart surgeries at 20% of the cost, but with quality that equals that of New York hospitals.

However, these and other more game-changing innovations representing ‘affordable excellence’ can’t find a place in the current GII matrix.

In the current innovation matrix, as regards knowledge creation, only the knowledge created by formal systems is considered. This is simply because resource-poor people are considered ‘sinks’ and not ‘sources’. The National Innovation Foundation (nif.org.in) has posted over 20,000 such innovations by the people, for the people, with some of them having made a big difference. This shows that minds on the margin are not marginal minds and that their creations cannot be excluded from standard innovation matrices. We must find a way to include innovations resulting from this valuable source and also recognise the creation of robust national systems and processes (e.g. Grassroots Innovation Augmentation Network, micro venture capital funds) that ensure that socio-economic benefits can ultimately reach and benefit all of humanity.

The new indicators must also take into account innovations that will be needed to survive and succeed in the post-pandemic world. For example, rapid digitalisation has swept the whole world – developed as well as developing – and has influenced education, health, commerce, even lifestyles.

For education, for instance, we would need indicators for education content delivered and consumed online, skills garnered through online courses, start-ups delivering technology-led education, etc. These would be a better reflection of emerging global trends – apart from the currently used pupil-teacher ratio – which will have less weightage as digital learning takes over.

The geography of new knowledge creation is shifting from the developed world to talent-rich parts of the developing world. India, for instance, is becoming a global R&D hub, with over 1,200 multinational companies setting their R&D centers in India. Indian IQ is generating IP for these companies. Instead of (or in addition to) measuring expenditure of top three global companies on R&D (which is an input parameter), we should focus on output parameters for patents filed/granted, employment creation, and reversal of brain drain (reverse migration of skilled people, a great positive for the developing world).

What we have presented here are some thoughts on measuring and driving innovation by using parameters that go well beyond the conventional ones, like research papers, patents, high-tech exports, etc. The key objective is to drive the journey of ideas to impact, and ideas not from some privileged few, but from all, and impact, not on some privileged few but on all, and using not unidimensional innovation systems but multidimensional ones.

NO COMMENT