- Paired with remote-sensing technologies – trail cameras, drones, satellites – AI can improve the scope and the speed of environmental monitoring by analysing a large bulk of data almost instantaneously.

- Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST) has developed ecological AI, tentatively call “AI Ecologist”. This AI can identify and count the cranes in and around the Korean Demilitarised Zone.

- Currently, ecologists monitor the changes in the crane population by painstakingly counting the number of birds with their eyes and hands. It would help them greatly if AI could provide the population estimate. KAIST decided to apply the crowd counting algorithm, which is designed to count the human population, by analysing photographic images to count the crane population. The ecologists generously shared 1,500 crane photos to train the AI.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming ever more popular, from face-recognition applications on smartphones to security solutions. One underexplored but rapidly growing area for AI is its environmental use. Paired with remote-sensing technologies – trail cameras, drones, satellites – AI can improve the scope and the speed of environmental monitoring by analysing a large bulk of data almost instantaneously. Google has recently launched Wildlife Insight that develops ecological AI by collecting and analysing trail cam data across the world, while Microsoft runs a similar project called AI for Environment. We here at Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST) have also been developing ecological AI – which we tentatively call “AI Ecologist” – that can identify and count the cranes in and around the Korean Demilitarised Zone (DMZ).

Cranes in the DMZ

The Korean DMZ is a four-kilometer-wide and 248-kilometer-long territory across the Korean peninsula. It was established as a buffer zone at the end of the Korean War (1950-1953) to deter military conflicts between North and South Koreas. Remaining as a no-man’s land for over 70 years, the DMZ has now been transformed into a nature reserve, the “accidental” habitat for 91 endangered species. One of the wildlife in peril is the migratory cranes.

Red-crowned cranes (Grus japonensis) and White-naped cranes (Grus vipio) spend summer in Siberia and fly down to the DMZ and surrounding areas in winter (November to March). The grains from rice fields provide enough food resources, while the restored wetlands inside the DMZ offer safe resting places. The number of cranes has increased from several hundred in the 1990s to several thousand by now, making the DMZ and its vicinity one of the most important wintering sites for these internationally endangered species.

Red-crowned crane (left) and white-naped crane. Photo: Yoo Seung-Hwa

Cranes have long been highly appreciated in Korean traditional culture, viewed as a symbol of long life and good fortune. We had a good population of wintering cranes but lost most of them during the past century through colonial hunting, urbanisation, and the Korean War. Therefore, it was a welcome surprise that the cranes started to come again to the DMZ and surrounding areas.

However, the cranes in and around the DMZ are now faced with new challenges presented by human encroachment in their habitats – relaxed border controls, greenhouses, roads, and other infrastructure – in addition to the changing climate. Additionally, ecological monitoring of the cranes is fairly restricted due to security reasons as well as the remaining landmines inside the DMZ.

Counting cranes with AI

To improve the capacity of crane monitoring where ecologists have limited access, we turned to AI and trail cameras. Currently, ecologists monitor the changes in the crane population by painstakingly counting the number of birds with their eyes and hands. It would help them greatly if AI could provide the population estimate. We decided to apply the crowd counting algorithm, which is designed to count the human population by analysing photographic images to count the crane population. The ecologists generously shared 1,500 crane photos to train the AI.

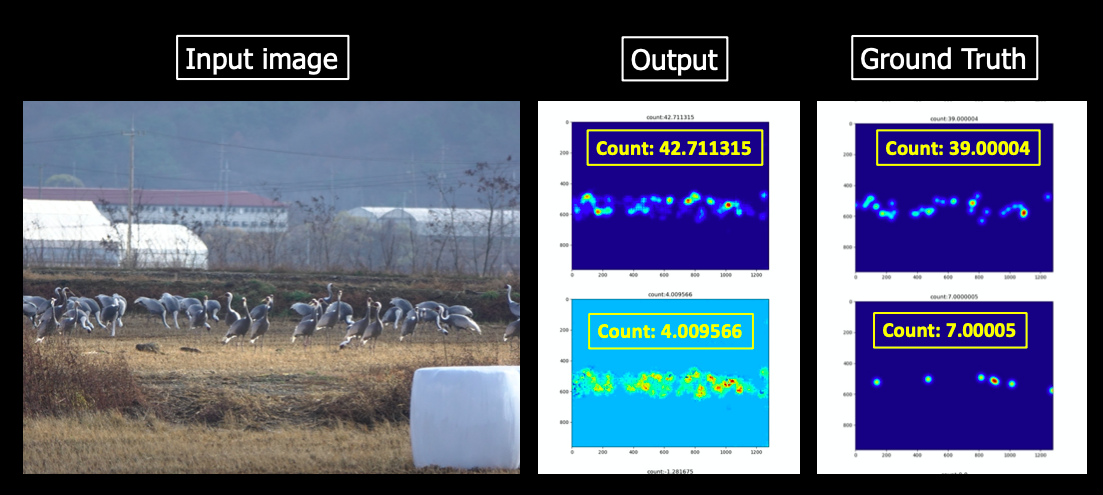

Here, in and around the DMZ, we have two different species of cranes, each of which has two distinctive age groups of juvenile and adult birds. To reflect these distinctive features, we trained the algorithm to be able to identify different species and age groups and count their number, respectively. This means that we have five classes – adult and juvenile red-crowned cranes, adult and juvenile white-naped cranes, and great white-fronted geese. After sets of training, the algorithm provides five class-specific density maps. By aggregating the weights assigned to the various colours of the dots, AI can provide the estimated population of each class.

Crane-counting algorithm

The image above shows how the AI works. In the input image, we have two classes – adult and juvenile white-naped cranes. The ground truth informs that the image contains 39 adult white-naped cranes and seven juvenile ones. Then the algorithm provides two density maps and the numbers: 42 for adults and 4 for juveniles. Voila! Not perfect yet, but it works.

Monitoring through trail cameras

The next step is to test and improve the crane counting algorithm to analyse trail camera data. Last winter, we set up 13 trail cameras in the rice fields and riverbanks of Cheorwon, Gangwon Province, where the majority of cranes spend winter. The cameras are located outside the DMZ to comply with the security restrictions. Crane-enthusiastic farmers, who have experience in monitoring devices, kindly allowed and helped us install trail cameras within their rice fields. While we cannot, the cranes fly over the fortified lines, making use of both the wetlands of the DMZ and rice fields just outside of it. One camera was installed at the crane observatory that watches over the Hantan River (Fig 3). This particular camera is set up and monitored in collaboration with the Graduate School of the University of Zurich. It records the changing landscape and wildlife of Hantan River for the upcoming exhibition in Zurich as well as the AI training at KAIST.

Trail camera at the Hantan River Crane Observatory

From a six-month operation, we have collected 97,000 photos and 23,858 short videos. At the moment, we are training the crane-counting AI to analyse the trail camera images. We learned from the trail run that the AI trained with human-taken images does not necessarily work well with machine-taken images. Ecologists’ photos and trail camera photos have some distinctive features in terms of their modes of operation, camera angles, and resolutions. Trail cameras expand the scope of environmental monitoring as they allow close-up observation of wildlife in remote locations, especially during the night. However, these remotely produced images pose extra challenges for AI that aims to identify and count the wildlife. We are searching out and applying leading-edge AI technologies to improve the AI to solve these difficult problems.

By developing AI for crane monitoring, we hope to illustrate the utility of, and the need for, wildlife monitoring assisted by remote-sensing devices and AI. Such technologies could help us better understand how wildlife persists in places such as the DMZ, where humans have limited access.

NO COMMENT