- Health diplomacy brings mutual benefits in managing crises, co-creating healthcare ecosystems and sharing health management experiences, connects societies and creates a platform for soft power, granting international and moral leverage to the cooperating countries.

- The success of Pop-up hospitals during COVID brings hope that this can help bridge the healthcare infrastructure lacuna in India, especially in remote areas. The utility and effectiveness of such models have been proven, and they may be the next tool in the Health Diplomacy initiatives from India.

The origins of Health Diplomacy

The concept of “medical diplomacy” was introduced as early as 1978 by Peter Bourne, special assistant to the President for health issues during the Carter administration, USA. According to the GHS Initiative in Health Diplomacy, UCSF (2008), “Health Diplomacy occupies the interface between international health assistance and international political relations. It is a political change agent that meets the dual goals of improving global health and helping repair failures in diplomacy, particularly in conflict areas and resource-poor countries.” However, while the terms of description are evolving, health diplomacy has been in practice for at least 100 years through international efforts to contain diseases like yellow fever, cholera and plague [1].

The need for Health Diplomacy

The term Global Health Diplomacy, or Health Diplomacy, emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s. In the aftermath of the Cold War, a new world order characterised by the abolition of borders in economic, technological, political, social, and cultural structures came into being. With more globalisation came the requirement for countries to work together to achieve health outcomes through cooperation. This was also in the aftermath of the AIDS crisis, the first truly international health crisis.

Steps taken by India: The landmark events in Health Diplomacy

India believed in health diplomacy much before the term was coined. As part of the Global South, which continues to bear high health costs due to inadequate health infrastructure, economic strangulation and exorbitant financial packages, India understands the value of health diplomacy as a tool to prevent, detect or respond to health issues. India’s geographical position also adds to this: it is located in a neighbourhood with several endemic conditions, is affected by massive natural calamities annually, suffers from malnutrition, and is deficient in healthcare infrastructure to tackle such major health challenges.

Thus, health diplomacy brings mutual benefits in managing crises, co-creating healthcare ecosystems and sharing health management experiences, and connects societies and creates a platform for soft power, granting international and moral leverage to the cooperating countries. Several initiatives launched by India, and its positioning with the UN add heft: through the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation programme [2] and bilateral cooperation, India has cooperated and invested in several scientific and health issues of developing countries. India is also an elected non-permanent member of the UNSC and chair of the World Health Organisation Executive Board.

India has already played a vital part in the SDG 3.8 [3], which pertains to “access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all”. 20 years ago, CIPLA India’s production and retailing of Antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) at less than $1 per day, provided countless more patients access to life-saving medication, a decisive step against HIV-AIDS [4]. This experience stood India in good stead during COVID: After addressing the needs of the 1.3 billion, Indian firms were in the position to export them globally within permissible standards at the most affordable prices. This included Vaccines, PPE Kits, and essential medications [5]. Clearly, the past lessons stood the Government of India in good stead.

However, it is essential to focus on emerging requirements and develop cost-effective solutions instead of having only reactive solutions.

Creating for India and the World

Despite strengths in pharma manufacturing and vaccine production, the Indian healthcare infrastructure is still lacking, particularly in remote areas, where people must travel long distances for minor and major health conditions. Healthcare infrastructure is disproportionately focused on urban areas, with 75% in cities while only 25% are in rural areas and there is a corresponding inverse in demographic spread [6]. The inequity of healthcare funds is a big reason.

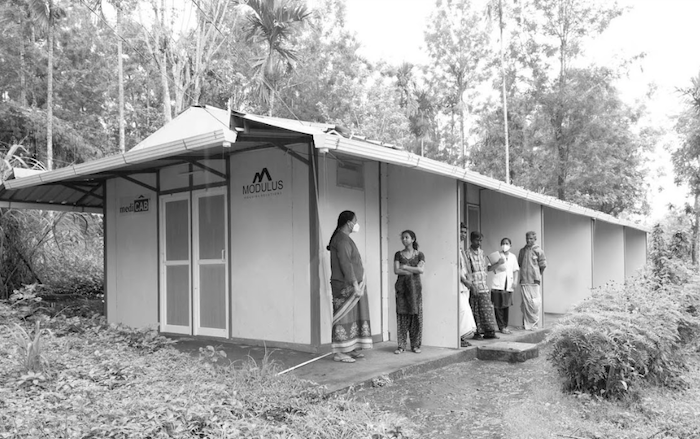

During COVID, the lack of infrastructure affected patients’ caregiving in cities and rural areas. IIT Madras-incubated startup Modulus Housing has developed a portable hospital unit called ‘MediCAB’ to treat COVID-19 patients. An initiative of the Office of Principal Scientific Advisor and the startup, this was meant to boost healthcare infrastructure by assisting states in setting up COVID-19 extension hospitals. MediCAB was launched in the Wayanad District of Kerala and collaborated with Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology (SCTIMST) [7].

It has now led to the development of 750+ micro hospitals that can be deployed rapidly across the nation, with installations in 20 states in India. The startup has worked with Habitats for Humanity as well [8].

The Road Ahead

Pop-up hospitals are familiar; they date back to at least 2014 but received a true fillip only during COVID. With their success comes the hope that they could be a crucial solution in bridging the healthcare infrastructure lacuna in India, especially in remote areas. The long-term impact would be in setting up such on-demand services in storm or flood-hit areas and making this the new norm of healthcare in resource-constrained settings.

A portable hospital unit called ‘MediCAB. Photo: Modulus Housing

This is not a stop-gap solution or a poor man’s ICU; this instead should be visualised for decentralised healthcare, a sustainable alternative to CapEx-heavy hospital infrastructures, and a crucial component of SDG 3.8.2 – Catastrophic Health Spending [9]. Given that one illness can send entire populations into poverty, rapid and localised treatment is imperative.

The utility and effectiveness of such models have been proven and may be the next tool in the Health Diplomacy initiatives from India. These novel models help bolster India’s healthcare loop from medicines to sustainably-built caregiving structures, which could be the next affordable healthcare setup for the Global South, customised to local requirements and decentralised for maximum, immediate impact.

References:

[1] Fidler DP. (2001). The globalisation of public health: the first 100 years of international health diplomacy. Bull World Health Organ, 79(9):842–9.

[2] https://www.itecgoi.in/index

[3] https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/service-coverage

[4] https://www.cipla.com/mission-care/ciplas-new-triple-combination-antiretroviral-drug-approved

[6] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1539877

[7] https://ddnews.gov.in/sci-tech/project-medicab-augmentation-hospital-infrastructure

[8] https://www.modulushousing.com/medicab

[9] https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/financial-protection

NO COMMENT