- Communities took the initiative to form neighbourhood WeChat groups to address daily challenges, such as food, medicine and supply purchases, PCR testing logistics, senior support, pet care, and more. Many used these platforms to share tips and best practices to help navigate the lockdown challenges.

- The Shanghai lockdown highlighted the importance of developing more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable digital platforms and initiatives to promote digital well-being and provide better support for the elderly population in a hyper-digitalised society.

- Group purchasing became a widespread social entrepreneurial practice across Shanghai. Before the lockdown, group purchasing constituted a means of purchasing with wholesale discounts, yet when all other supply channels were severed, this alternative shopping method became unexpectedly essential to survival.

Since late March 2022, Shanghai’s 25 million residents have been placed under stringent lockdown measures upon the emergence of the highly transmissible COVID-19 variant, Omicron SARS-CoV-2. The heavy-handed nature of the government-imposed measures and their lengthy extension has caught many people surprised and unprepared. This has been further compounded by a lack of infrastructural support and persisting logistic challenges, which have led to much suffering and various tragedies over the past weeks.

However, this article seeks to draw attention to the sparks of human ingenuity that are often ignited in times of crisis. This is particularly notable in the case of the Shanghai lockdown, where people are sealed away within their homes; these bottom-up, community-oriented innovations help ensure that fundamental human needs are met, propelled by a blend of necessity and creativity DIY resolve. Perhaps more importantly, we hope to bring to the fore some societal challenges posed by the digital oversaturation under these conditions, to encourage initiatives towards more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable responses to future crisis situations.

Adversity as a Catalyst for Innovation

The early days leading up to the eventual full-city lockdown were fraught with uncertainties. Shanghai had previously enjoyed relatively relaxed pandemic measures compared to the rest of the country, so when a staggering half-city Pudong-Puxi lockdown was announced in late March, many assumed it would be a rather brief and painless ordeal. As it turned out, it was not.

Within the first weeks of the lockdown, China’s extensive eCommerce industry was brought to its knees, as local online shopping platforms and logistics systems came to a standstill, plagued by labour shortages and new restrictions that impeded last-mile delivery. At the community level, the local residential committees (居委会), the lowest level of governance that maintains social order and ensures basic needs are met, were woefully understaffed (1 person for 1’000+ residents in many cases). They were often left to interpret and execute governmental directives passed down through the chain of command. As the days went by and the frequency of testing increased, more and more positive cases were reported, and the safety measures were tightened as citizens were asked not to leave their homes, let alone the residential building.

These dire circumstances drove many residents to take matters into their own hands. Communities took the initiative to form neighbourhood WeChat groups to address daily challenges, such as food, medicine and supply purchases, PCR testing logistics, senior support, pet care, and more. Many used these platforms to share tips and best practices to help navigate the challenges introduced by the new status quo that had upended nearly every aspect of daily life.

“Necessity is the mother of invention.” As testified by the time-honoured adage, the threat of losing access to basic needs, such as food and supplies, was a key motivating factor for many people. Many homespun solutions – often conceived with no intention towards scalability – picked up traction through the digital grapevine of WeChat groups and other channels.

“I wake up at 5:30 am every morning to resume my endless quest for groceries, juggling between different mobile apps. I was able to succeed once at the very beginning of the lockdown – a huge triumph that we celebrated as a family. But success has evaded us since then. I’ll consider using a massage gun [to help rapidly tap the apps’ checkout button] tomorrow, I heard it will help.” – Ms. Li

Massage gun – finger combo for rapid shopping cart checkout

Further to these makeshift solutions, some enterprising coders also took a more hi-tech approach by writing scripts to simultaneously monitor multiple shopping apps and automate their checkout processes.

Meanwhile, as resources became increasingly scarce, many emergent innovations sought to make the most of existing supplies. Digital-enabled bartering evolved commonplace. People started trading cabbage for coffee capsules or disinfecting wet wipes for soya sauce in an increasingly impersonal metropolis where you seldom know your next-door neighbour. In the lobby of some buildings, the residents’ designated space for the free trading of items, where people could take and leave goods as needed. In others, the residents hung a bag on their front door handle to facilitate zero-contact trading.

“I strived to provide an organic lifestyle for my family. Now we simply need some food.” – Mr. Wang

Some sustainably-minded individuals started cultivating vegetables and herbs in a “home garden” despite the limited space, consuming the leaves and trimmings while leaving the stalk and stem to continue growing them in either soil or water. Keeping the vegetable supplies growing in water (hydroponic gardening) also served as an effective food storage method to preserve bulk orders under room temperature, freeing up valuable refrigerator space during the lockdown.

Makeshift home garden in a high-rise

To help people overcome their daily lockdown challenges, new Mini Programs were created within the WeChat ecosystem. For instance, many Shanghai residents, especially young professionals, had grown reliant on the city’s robust food delivery (外卖) system, remained uninitiated in the culinary arts, and lacked large enough refrigerators to store food supplies. All the while, the logistic stranglehold placed limitations on the available ingredients. In lieu of a crash course on Cooking 101, a handy WeChat Mini Program, “Homebody Recipes” (宅家食谱), was circulated to recommend cooking recipes based on the essential ingredients one had at hand.

“Homebody Recipes” app

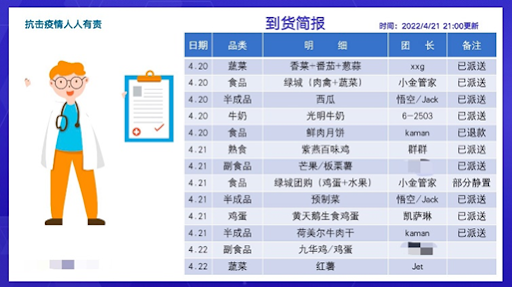

Finally, group purchasing became a widespread social entrepreneurial practice across Shanghai. Before the lockdown, group purchasing constituted a means of purchasing with wholesale discounts, yet when all other supply channels were severed, this alternative shopping method became unexpectedly essential to survival. Specifically, it was typically coordinated and operated at the neighbourhood WeChat group level with more than 100 participants. It was dedicated to specialised functions such as purchasing milk, eggs, vegetable combos, staples, proteins, etc. The volunteer leader of a group (团长) – usually a resourceful and well-connected individual – took up the responsibilities of confirming supplies from local farmers and vendors, collecting orders and payments from group members, placing the order, and verifying delivering the goods assisted by other volunteers.

Originally organised using WeChat’s built-in message queuing function (接龙), this was later integrated into various Mini Programs from group purchase companies such as Pinduoduo (拼多多) and Kuaituantuan (快团团) that helped standardise and formalise the procedure. As the lockdown progressed, residents in many compounds created and continually improved upon their Standard Operating Procedures for group purchase endeavours, including daily flyers on the consignment of goods.

Example of daily delivery consignment report

In virtually all these instances, the social innovations were greatly enabled and propagated by digital platforms. However, it is equally important to consider the flip side of digital oversaturation, namely the adverse effects that over-exposure to social media can have on the collective mental health, as well as the potential neglect of a senior population, which is often less accustomed to digital devices and services.

Social Challenges of Digital-Centric Innovation

From the onset of the outbreak, people’s well-being and mental health were strained due to a myriad of reasons, ranging from restrictive distancing and confinement measures to psychological burdens brought on by physical inactivity and nutrition insecurity. This was further exacerbated by technology-induced anxiety in a hyper-connected digital society, which could arise from several root causes.

Firstly, the group purchases on WeChat and community PCR tests are usually initiated at unannounced and irregular time intervals in different WeChat groups throughout the day. The persistent vibrating and flashing of notifications, in turn, constantly distracts people from what they are doing, leading to disrupted memories and cognition. This often leads to the feeling of apprehension associated with the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), commonly attributed to social interactions but in these instances, is tied to the anxiety over missing out on access to material goods.

Secondly, there is an over-dependence on social channels for outside information, which can often be falsified or misleading, as people are glued to the screens of their devices, too anxious to let anything slip by. This can often lead to a downward spiral, as individuals afflicted with mental stress plunge into further information consumption to alleviate their feelings of uncertainty, which are further stress-inducing. There has also been a noticeable increase in demand for mental health support, as psychological consultancies and medical institutions have started to provide free services online, such as by offering counselling on their websites or by building up WeChat groups.

Meanwhile, the elderly population has been especially vulnerable and at-risk in crisis situations. They face more chronic health conditions that can become life-threatening and are often reliant on communal support. However, they are also very often unfamiliar with digital platforms, opting instead to rely on more conventional methods for communications and transactions.

In the case of the Shanghai lockdown, this digital divide has proven to be a significant hurdle for many seniors as life shifts swiftly and unapologetically online. Elderly people living alone face a longstanding inequality in the access to and digital literacy in the new digital tools put in place to support everyday life, such as Covid Test QR Codes, WeChat Groups for new policy updates, food and supplies purchases, and social exchange.

Digital healthcare solutions set up during the lockdown have been remarkably challenging to navigate for their main target demographic. Some neighbourhoods have organised volunteer groups to take care of the elderly who live by themselves, listen to their needs, purchase daily necessities, and provide companionship. However, this is usually far from sufficient. As China’s ageing population continues to grow, it calls for more inclusive digital platforms and assistive technologies and initiatives that can help bridge the digital divide.

Volunteer offering a pack of noodles to a senior citizen who is only accustomed to cash

Reflections & Future Outlook

The Chinese word for ‘Crisis’ (危机) is composed of two characters representing ‘danger’ (危) and ‘opportunity’ (机). At the time of writing this, in the first week of May, most business activities remain shuttered, creating an enormous impact upon the global economy and supply chains and drawing the lion’s share of international media attention.

However, the various grassroots social innovations arising out of the lockdown have also created an informal economy and society that operates more subtly at the community level and has fundamentally changed how people go about their daily lives. The dangers emerging from the current crisis may allow people to rediscover and reassess their basic needs in evolving different models to meet those demands and, therefore, help alleviate systemic deficiencies well beyond the lockdown situation.

Artist’s rendition of the Shanghai Lockdown

NO COMMENT